“My angel!” A woman’s voice is heard outside a hut in the snow in Kashmir in 1995, a landscape devoid of colors other than mostly black, white, and deep blue. Ghazala’s son, Haider, a lone fighter, is hiding inside the severely damaged hut. Having sustained gun-shot wounds, he is surrounded by the soldiers led by his uncle Khurram who plans to kill him with a shoulder-launch rocket, but Ghazala, caught in between her lover and her son who is intent on avenging his father’s death, convinces Khurram to give her one last chance to persuade Haider to give up his revenge plan and surrender. Soft spoken, Ghazala may not appear to be a particularly strong woman at first glance, but she is taking on the active role of a liaison, negotiator, and now a game changer.

“My angel!” A woman’s voice is heard outside a hut in the snow in Kashmir in 1995, a landscape devoid of colors other than mostly black, white, and deep blue. Ghazala’s son, Haider, a lone fighter, is hiding inside the severely damaged hut. Having sustained gun-shot wounds, he is surrounded by the soldiers led by his uncle Khurram who plans to kill him with a shoulder-launch rocket, but Ghazala, caught in between her lover and her son who is intent on avenging his father’s death, convinces Khurram to give her one last chance to persuade Haider to give up his revenge plan and surrender. Soft spoken, Ghazala may not appear to be a particularly strong woman at first glance, but she is taking on the active role of a liaison, negotiator, and now a game changer.

Family issues and personal identity are tragically entangled in terrorism, politics, and national identity when Haider responds to his mother’s plea that “there is no greater pain than to see the corpse of your own child” by re-asserting that he cannot “die without avenging the murder of one’s father.” His moral compass is clearly pointing in a different direction. His mother does not believe politics should and can take precedence over love. His mother’s love is apparent, but it is not enough to change Haider’s mind. In her desperate last attempt to turn her son around, Ghazala spells out what is one of the most significant themes of Vishal Bhardwaj’s 2014 film Haider: “revenge begets revenge; revenge does not set us free. True freedom lies beyond revenge.” The clash between the mother’s and her son’s worldviews is tragic.

Like Hamlet, Haider explores dramatic ambiguity: How much does the Gertrude figure know about Claudius’s plan to kill Hamlet? Does she consciously intervene to save Hamlet? If so, does her act of self-sacrifice give her more agency in a men’s world? As Tony Howard points out, Haider’s ending “poses uncomfortable contemporary questions about suicide and revenge—and the ability of Shakespeare’s texts to help us answer them” (51). The ending of Haider is ambiguous, as we are not shown whether or how Haider finds a new path in life.

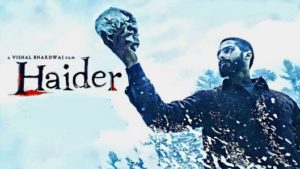

Haider’s life experience and identity are full of paradoxes. The film engages with the notion of duality. Ironically, Haider’s Muslim family send him away to university in the hope that he would not be religiously and politically radicalized. A student of “revolutionary poets of British India” (as he tells the Indian guard at the checkpoint), Haider returns to his homeland of militarized Kashmir in the midst of mid-1990s Pakistan-India conflicts upon the news of his dissident father’s disappearance. Even the props carry this duality. Arshia (Ophelia) knits her father a red scarf, which he wears often proudly. However, the same scarf is used to tie up Haider’s hands in a later scene. Many scenes, shot on site in Kashmir, are largely devoid of colors and overwhelmed by the weight of politics. Politics means there are always more than two sides to the story. Haider finds his mother in a relationship with his uncle, a high-ranking official. The play-within-a-play and gravedigger scenes are staged in the form of musical numbers. Directed by Vishal Bhardwaj and written by the Kashmiri journalist Basharat Peer, Haider (UTV Motion Pictures, India, 2014; in Hindi and Urdu) is one of the latest Asian Shakespeare films.

================================

Excerpted from Alexa Alice Joubin, “Shakespeare on Film in Asia.” Chapter 12 of The Shakespearean World, ed. Jill L. Levenson and Robert Ormsby (London: Routledge, 2017), pp. 225-240; free and open-access full text Opens in a new window

================================